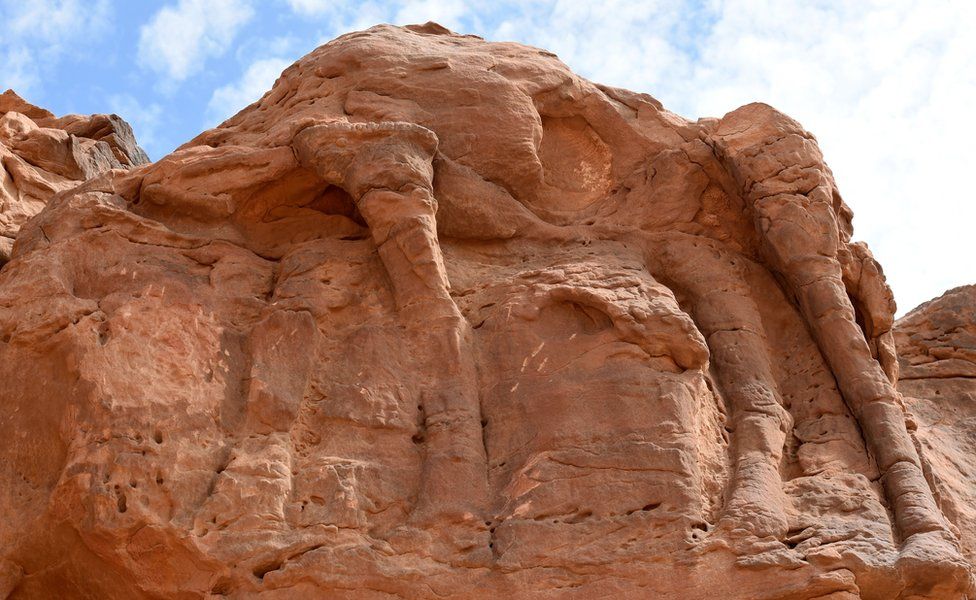

These life-sized camel carvings on Al-Jouf’s desert rocks date back to 8,000 years. Here’s everything you need to know about the camel site, a piece of history older than the Stonehenge and Egyptian pyramids.

Discovery of camel site in Saudi Arabia

The camel site was first discovered in Northern Saudi Arabia in 2018. At first, researchers assumed that they dated back to 2,000 years ago. However, new research proves otherwise. Researchers used a wide range of new dating methods and established that the carvings were from the Neolithic age. The carvings were found to be much older for the site and go back to the final division of the Stone age. A total of 21 relics were identified including several carvings of camels and equids. However, the artwork has a resemblance to work found in Petra and Jordan hence, it was dated back to the Nabataean period.

The team was led by researchers from the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History, King Saud University, and the Saudi Ministry of Culture. Additionally, research reveals that most of them were carved before the late 6th millennium BC. This makes the Camel reliefs the “oldest surviving large-scale reliefs” in the world.

More on the new archaeological discovery

The discovery of the “oldest surviving large-scale reliefs” is monumental. After all, the camel sculptures are now older than major ancient landmarks. This includes the 4,500 years old Pyramids of Giza and the 5,000-year-old Stonehenge. However, the Camel site comes with its ancient mysteries which motivate the researchers to keep digging and uncovering secrets. Unfortunately, the task is a challenge since the erosion causes damage to the site. The erosion led to the abundant destruction of the archeological landscape.

“Our results show that the reliefs were carved with stone tools. The creation of the reliefs, as well as the main period of activity at the site, dating to the Neolithic. Neolithic arrowheads and radiocarbon dates attest occupation between 5200 and 5600 BCE.” stated the study. “We can now link the Camel Site to a period in prehistory when the pastoral populations of northern Arabia created rock art. Additionally, they built large stone structures called mustatil,” said the authors.

“The Camel Site is, therefore, part of a wider pattern of activity where groups frequently came together to establish and mark symbolic places,” they added. “Preservation of this site is now key. As is future research in the region to identify if other such sites may have existed. Time is running out on the preservation of the Camel Site and on the potential identification of other relief sites. After all, the damage will increase and more reliefs will be lost to erosion with each passing year,” said Dr. Maria Guagnin. Gauguin is a researcher of Human History at the Max Planck Institute for Science in Germany.