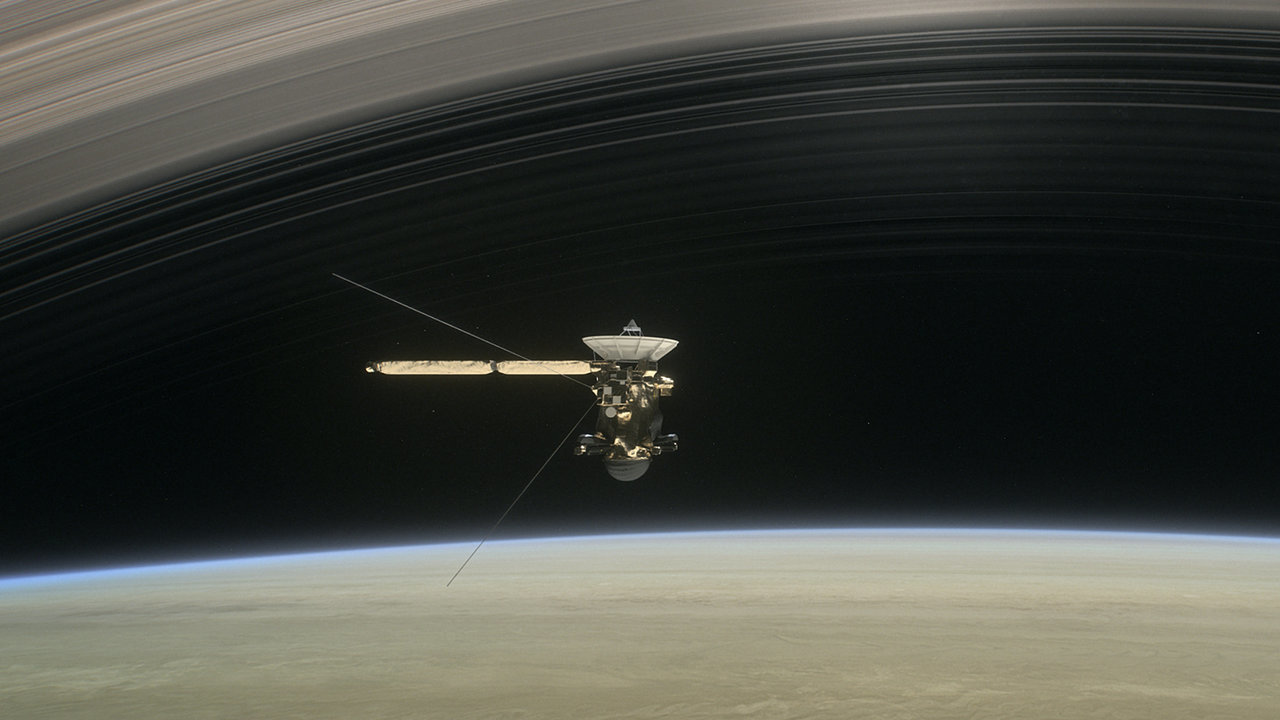

A new study shows methane gas wafting from Enceladus, one of Saturn’s moons is a sure shot sign of alien life. NASA’s Saturn orbiter Cassini discovered several geysers blasting water ice particles into space in 2005. It occurred from the tiger stripe fractures near the south pole of Enceladus. Read to know all about it.

Discoveries made by NASA’s Cassini

The plume feeding into Saturn’s second outermost ring comes from a huge reserve of liquid water which sloshes under the icy shell of the moon. Moreover, it is not just water ice in the plume. During a total of 313 mile wide flybys, the orbiter spotted several components. It includes di-hydrogen and organic compounds containing carbon like methane. “We wanted to know: Could Earth-like microbes that ‘eat’ the dihydrogen and produce methane explain the surprisingly large amount of methane detected by Cassini?” said Régis Ferrière, the co-lead of the study. Ferrière is an associate professor at the Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology of the University of Arizona.

The proof behind the possibility of alien life on Saturn‘s moon

Studies suggest that dihydrogen, produced by the contact between hot water and rock in the vents of the moon. Moreover, this is very similar to how life originated on planet Earth. Additionally, dihydrogen provided energy for microbes on Earth. These microbes can make methane from carbon dioxide. Something similar might have been occurring on Enceladus since the orbiter found CO2 and methane in its plume.

Stimulations obtained by mathematical models in the study asses that the methane found on the moon was biological. It shows that dihydrogen production can strain the microbe population on Enceladus. “In summary, not only could we evaluate whether Cassini’s observations are compatible with an environment habitable for life, but we could also make quantitative predictions about observations to be expected, should methanogenesis occur at Enceladus’ seafloor,” added Ferrière.

The study also determined that abiotic vent chemistry occurring on Earth does not explain the methane concentration observed by Cassini. However, the contributions of methane-producing microbes close the gap.