The creation of life on earth has always been a fascinating subject. It seems like the world has found something new in its research. Scientists have discovered the biggest molecule ever observed in a planet-forming disk in the new research.

Leiden University in the Netherlands in partnership with the European Southern Observatory carried out the research. The journal Astronomy and Astrophysics published the findings.

Researchers in Chile used the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) to identify dimethyl ether in a planet-forming disc for the first time.

This is the largest molecule in such a disc yet, with nine atoms. It’s also a precursor to larger organic molecules, which could lead to the birth of life.

“From these results, we can learn more about the origin of life on our planet and therefore get a better idea of the potential for life in other planetary systems,” says astronomer Nashanty Brunken.

Bigger picture of bigger molecule

“It is very exciting to see how these findings fit into the bigger picture.”

Dimethyl ether is a common organic molecule in star-forming clouds. But it has never been discovered in a planet-forming disc before. The researchers also detected methyl formate. It is a complex molecule that is a building component for even larger organic compounds. The molecule is similar to dimethyl ether.

“It is really exciting to finally detect these larger molecules in discs. For a while we thought it might not be possible to observe them,” explains co-author Alice Booth.

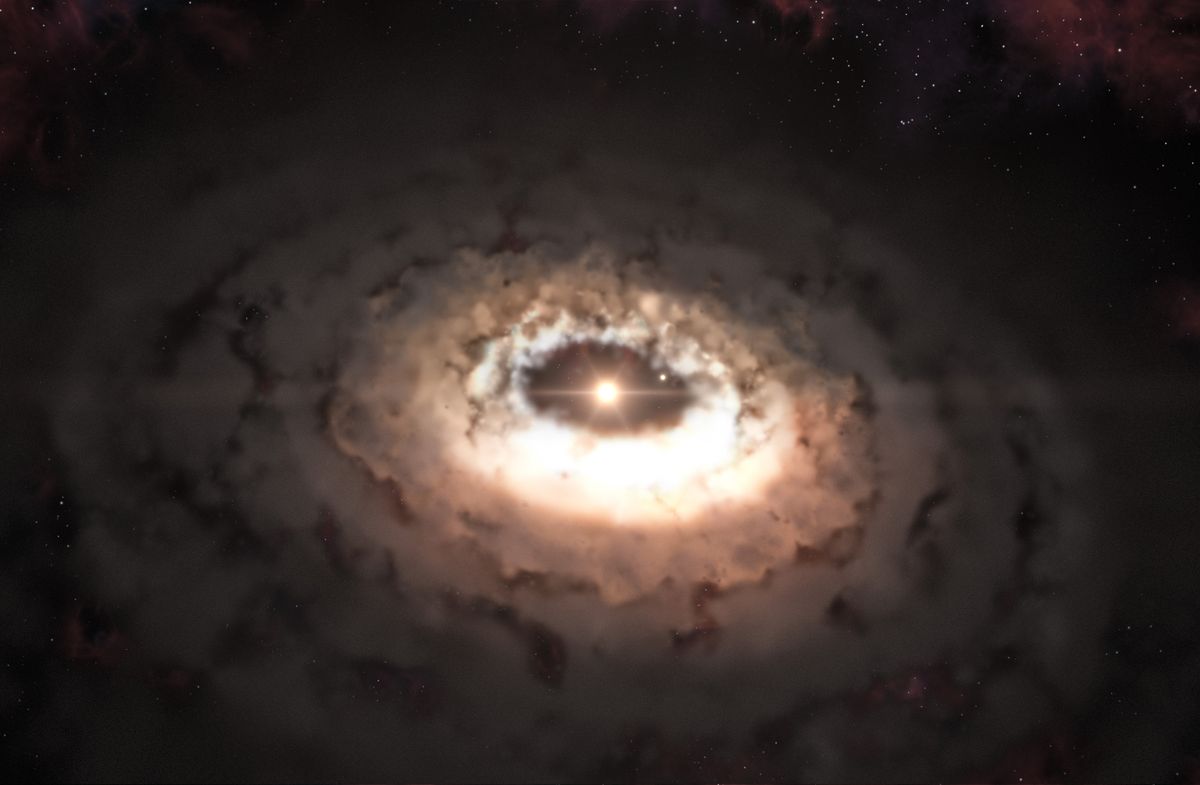

With the help of ALMA, the molecules were discovered in the planet-forming disc surrounding the young star IRS 48. It is recognized as Oph-IRS 48.

Its disc contains an asymmetric, cashew-nut-shaped “dust trap”. IRS 48, situated 444 light-years away in the constellation Ophiuchus, has been the subject of multiple research.

This region is likely to have formed as a result of a newly born planet or small companion star passing between the star and the dust trap. It holds a large number of millimeter-sized dust grains. They can collide and grow into kilometer-sized objects like comets, asteroids, and possibly even planets.

“What makes this even more exciting is that we now know these larger complex molecules are available to feed forming planets in the disc,” Booth says. “This was not known before as in most systems these molecules are hidden in the ice.”