NASA images reveal a shocking record of summer melting in Norway. Here’s everything you need to know about the situation.

Summer melt in Norway’s ice-covered archipelago

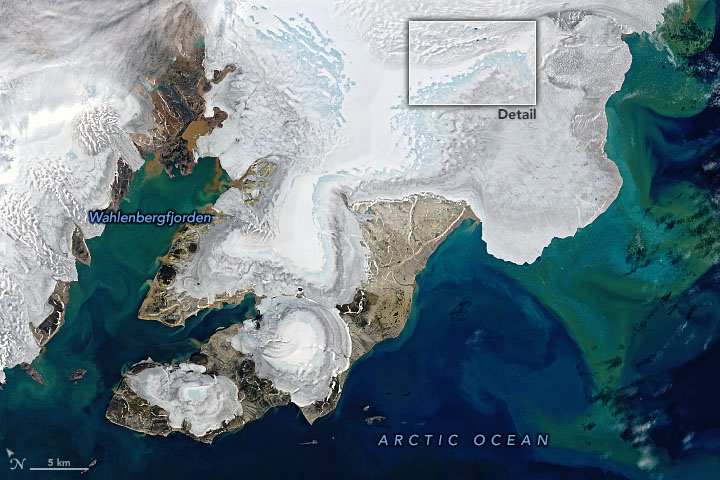

The unusually warm air temperatures of summer 2022 are leading to a record summer melt through Svalbard. Svalbard is a Norwegian archipelago in the Arctic Ocean and the home to the global seed vault. Additionally, it is one of the northernmost inhabited places in the world. The region had meltwater as a manifestation of the rapidly changing climate. Prior to this, the environment was altered by global warming.

Glaciers are receding and their surface layer or “firn” is losing its ability to hold in the meltwater. This year’s summer melting was a result of a consistent warm breeze from the south. Moreover, some parts of the archipelago experienced an average of up to 3.2 F higher temperature than usual. Additionally, it reached a record high summer melt volume following a significant warming trend from July 15.

What is the reason behind this?

There are several vital elements that are causing the surprisingly high volume of summer melt. The archipelago’s sea ice is disappearing sooner than ever before. By the end of spring 2022, the open ocean water was visible. Usually, sea ice is around until the end of summer. This in turn is responsible for allowing the warm southern winds to blow directly over the archipelago’s land without cooling down. Usually, the presence of sea ice cools down the southern winds. In addition to this last winter had lower snowfall.

With the warming weather, the thin snow covering quickly melted and revealed stretches of the older firm and bare ice. This region is darker and allows the absorption of a higher amount of solar radiation than fresh and bright snow. hence, accelerating the summer melt during sunny days. After all, in the part, the meltwater would be in the firn layer and soon re-freeze. Allowing the region to maintain glacier ice and prevent the water from going to the ocean. Between 1921 and 2010, Svalbard held on to about 34 percent of summer meltwater. However, this summer, the numbers were as low as eight percent. “The melt anomaly is 3.5 times larger than the 1981–2010 average, and 5 times the interannual variability. Only a changing climate can explain this,” stated Xavier Fettweis. Fettweis is a climatologist at the University of Liège.