Scientists have found the RNA sample that potentially helps resuscitate the carnivorous animal, formally known as a thylacine, which went extinct over 100 years ago. Ribonucleic acid (RNA) is a genetic substance found in all living cells that resembles DNA in structure. Scientists hope to resurrect the extinct mammal using improvements in genetics, ancient DNA retrieval, and artificial reproduction. They extracted RNA from the dried skin and muscle of a Tasmanian tiger kept in a Swedish museum since 1891.

“We would strongly advocate that first and foremost we need to protect our biodiversity from further extinctions, but unfortunately we are not seeing a slowing down in species loss,” said Andrew Pask, a professor at the University of Melbourne and head of its Thylacine Integrated Genetic Restoration Research Lab, who is leading the initiative, reports CNN. “This technology offers a chance to correct this and could be applied in exceptional circumstances where cornerstone species have been lost,” he added.

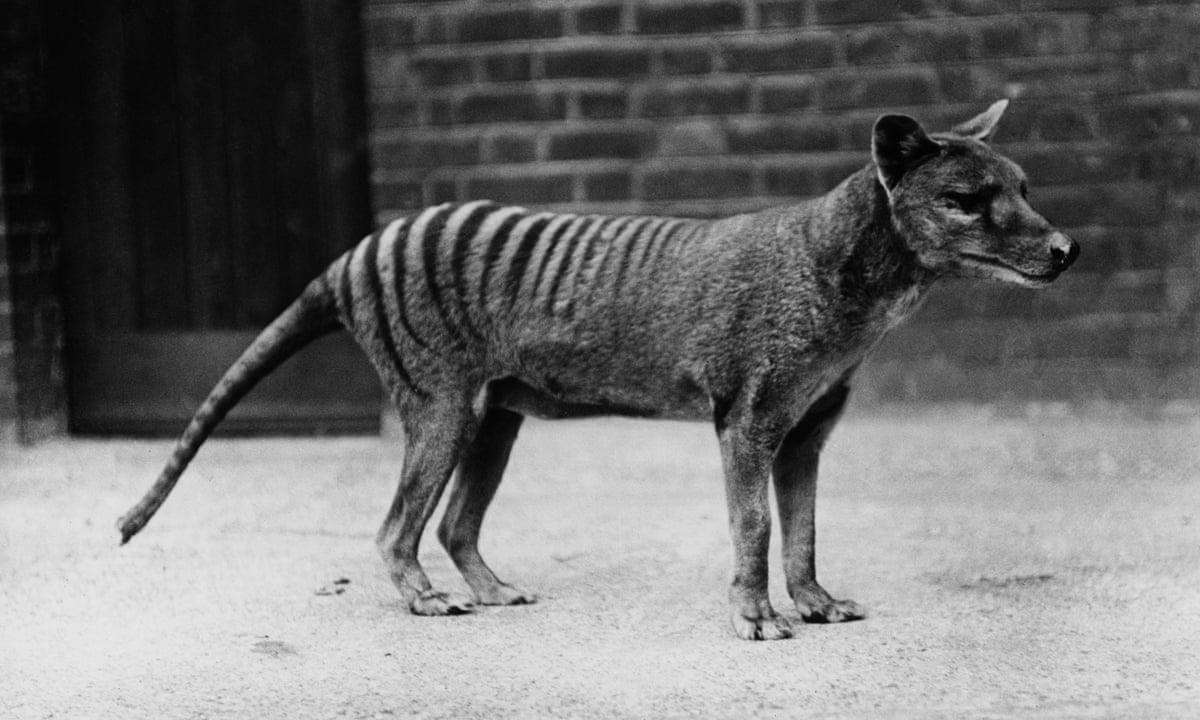

The Tasmanian tiger resembled a wolf except for the tiger-like stripes on its back

The initiative is being carried out in conjunction with Colossal Biosciences, a Texas-based company formed by tech entrepreneur Ben Lamm and Harvard Medical School geneticist George Church. Both have invested over $15 million in resurrecting the woolly mammoth in a modified form. Except for the Australian island of Tasmania, the Tasmanian tiger, which is roughly the size of a coyote, vanished around 2,000 years ago. It served an important role in its ecology as the only marsupial apex predator that lived in modern times, but this also made it unpopular with people.

In the 1800s, European settlers in Australia chased the secretive and semi-nocturnal Tasmanian tigers, blaming them for livestock losses. However, there has been no evidence linking livestock losses to Tasmanian tigers. Benjamin, the last thylacine in captivity, died of exposure in 1936 at the Beaumaris Zoo in Hobart, Tasmania. This catastrophic loss occurred soon after thylacines were awarded protected status, but it was too late to save the species. The Tasmanian tiger resembled a wolf except for the tiger-like stripes on its back. People arrived in Australia approximately 50,000 years ago, resulting in significant population losses.